Shannon's source coding theorem

In information theory, Shannon's source coding theorem (or noiseless coding theorem) establishes the limits to possible data compression, and the operational meaning of the Shannon entropy.

The source coding theorem shows that (in the limit, as the length of a stream of independent and identically-distributed random variable (i.i.d.) data tends to infinity) it is impossible to compress the data such that the code rate (average number of bits per symbol) is less than the Shannon entropy of the source, without it being virtually certain that information will be lost. However it is possible to get the code rate arbitrarily close to the Shannon entropy, with negligible probability of loss.

The source coding theorem for symbol codes places an upper and a lower bound on the minimal possible expected length of codewords as a function of the entropy of the input word (which is viewed as a random variable) and of the size of the target alphabet.

Contents |

Statements

Source coding is a mapping from (a sequence of) symbols from an information source to a sequence of alphabet symbols (usually bits) such that the source symbols can be exactly recovered from the binary bits (lossless source coding) or recovered within some distortion (lossy source coding). This is the concept behind data compression.

Source coding theorem

In information theory, the source coding theorem (Shannon 1948)[1] informally states that:

- "N i.i.d. random variables each with entropy H(X) can be compressed into more than N H(X) bits with negligible risk of information loss, as N tends to infinity; but conversely, if they are compressed into fewer than N H(X) bits it is virtually certain that information will be lost." (MacKay 2003, pg. 81[2],Cover:Chapter 5[3]).

Source coding theorem for symbol codes

Let  ,

,  denote two finite alphabets and let

denote two finite alphabets and let  and

and  denote the set of all finite words from those alphabets (respectively).

denote the set of all finite words from those alphabets (respectively).

Suppose that X is a random variable taking values in  and let f be a uniquely decodable code from

and let f be a uniquely decodable code from  to

to  where

where  . Let S denote the random variable given by the wordlength f(X).

. Let S denote the random variable given by the wordlength f(X).

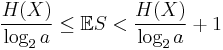

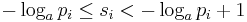

If f is optimal in the sense that it has the minimal expected wordlength for X, then

(Shannon 1948)

Proof: Source coding theorem

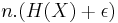

Given  is an i.i.d. source, its time series X1, ..., Xn is i.i.d. with entropy H(X) in the discrete-valued case and differential entropy in the continuous-valued case. The Source coding theorem states that for any

is an i.i.d. source, its time series X1, ..., Xn is i.i.d. with entropy H(X) in the discrete-valued case and differential entropy in the continuous-valued case. The Source coding theorem states that for any  for any rate larger than the entropy of the source, there is large enough

for any rate larger than the entropy of the source, there is large enough  and an encoder that takes

and an encoder that takes  i.i.d. repetition of the source,

i.i.d. repetition of the source,  , and maps it to

, and maps it to  binary bits such that the source symbols

binary bits such that the source symbols  are recoverable from the binary bits with probability at least

are recoverable from the binary bits with probability at least  .

.

Proof for achievability

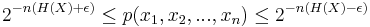

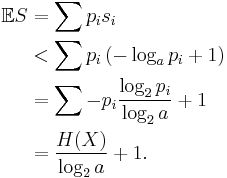

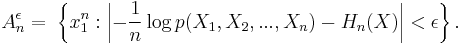

Fix some  . The typical set,

. The typical set, , is defined as follows:

, is defined as follows:

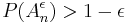

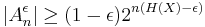

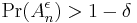

AEP shows that for large enough n, the probability that a sequence generated by the source lies in the typical set, , as defined approaches one. In particular there for large enough n,

, as defined approaches one. In particular there for large enough n,  (See AEP for a proof):

(See AEP for a proof):

The definition of typical sets implies that those sequences that lie in the typical set satisfy:

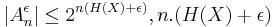

Note that:

- The probability of a sequence from

being drawn from

being drawn from  is greater than

is greater than

since the probability of the whole set

since the probability of the whole set  is at most one.

is at most one.

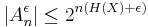

. For the proof, use the upper bound on the probability of each term in typical set and the lower bound on the probability of the whole set

. For the proof, use the upper bound on the probability of each term in typical set and the lower bound on the probability of the whole set  .

.

Since  bits are enough to point to any string in this set.

bits are enough to point to any string in this set.

The encoding algorithm: The encoder checks if the input sequence lies within the typical set; if yes, it outputs the index of the input sequence within the typical set; if not, the encoder outputs an arbitrary  digit number. As long as the input sequence lies within the typical set (with probability at least

digit number. As long as the input sequence lies within the typical set (with probability at least  ), the encoder doesn't make any error. So, the probability of error of the encoder is bounded above by

), the encoder doesn't make any error. So, the probability of error of the encoder is bounded above by

Proof for converse The converse is proved by showing that any set of size smaller than  (in the sense of exponent) would cover a set of probability bounded away from 1.

(in the sense of exponent) would cover a set of probability bounded away from 1.

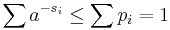

Proof: Source coding theorem for symbol codes

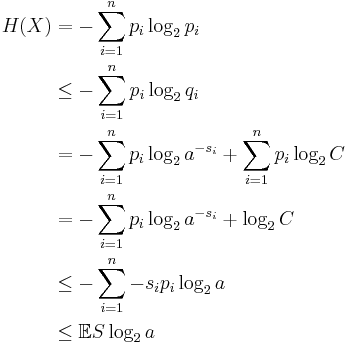

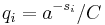

Let  denote the wordlength of each possible

denote the wordlength of each possible  (

( ). Define

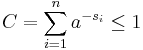

). Define  , where C is chosen so that

, where C is chosen so that  .

.

Then

where the second line follows from Gibbs' inequality and the fifth line follows from Kraft's inequality:  so

so  .

.

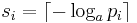

For the second inequality we may set

so that

and so

and

and so by Kraft's inequality there exists a prefix-free code having those wordlengths. Thus the minimal S satisfies

Extension to non-stationary independent sources

Fixed Rate lossless source coding for discrete time non-stationary independent sources

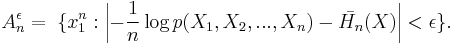

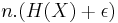

Define typical set  as:

as:

Then, for given  , for n large enough,

, for n large enough,  . Now we just encode the sequences in the typical set, and usual methods in source coding show that the cardinality of this set is smaller than

. Now we just encode the sequences in the typical set, and usual methods in source coding show that the cardinality of this set is smaller than  . Thus, on an average,

. Thus, on an average,  bits suffice for encoding with probability greater than

bits suffice for encoding with probability greater than  , where

, where  can be made arbitrarily small, by making n larger.

can be made arbitrarily small, by making n larger.

See also

References

- ^ C.E. Shannon, "A Mathematical Theory of Communication", Bell System Technical Journal, vol. 27, pp. 379–423, 623-656, July, October, 1948

- ^ David J. C. MacKay. Information Theory, Inference, and Learning Algorithms Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-521-64298-1

- ^ Cover, Thomas M. (2006). "Chapter 5: Data Compression". Elements of Information Theory. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-24195-4.